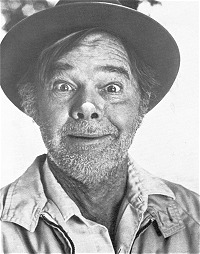

Personal Foreword: Sam Edwards, stepfather and loving example to my sisters and myself, and long-time faithful and genuinely kind husband to my mother, left our lives on July 28, 2004, around 9:22 am MDT in Durango, Colorado. While I had the direct benefit of being affected by his positive presence throughout most of my life, having taken his name early on in tribute, there are many others in the world who also were touched by one or more of his performances at some time. This page is largely complete as of this date (10/28/2019), but will expand a little if more information is collected. Additional information from census records and newspaper articles has been added as of that date to fill in the time line better. A full memoir/biography in print form and as an e-book is currently in the works for 2020 and is nearly complete. It will be more than ten times the length of this one, and contain a great many more photographs and stories about the ultimate character actor and his friends. Please honor his memory, and perhaps even jog yours, as you read through this short biography and remembrance.

Thank You So Very Much,

|

The Face Is Familiar, But I Can't Place the Name

Memories of a Hollywood Character Actor

by Beverly Edwards and Bill Edwards

by Beverly Edwards and Bill Edwards

Contents Copyright ©2004/2014/2019 by William G. Edwards

|

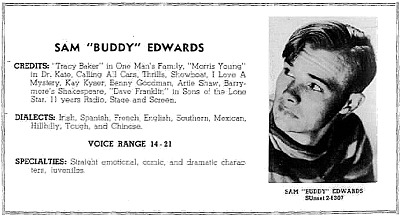

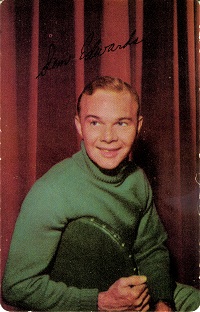

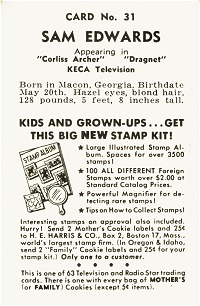

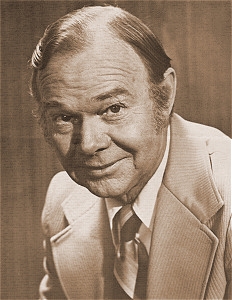

Sam Edwards, a long-time radio/movie/television character actor, died July 28, 2004, from heart complications at Mercy Hospital in Durango, Colorado, where he resided. He was 89. Best known to radio audiences in the 1940s and 1950s as the perennial teenager Dexter on the long running CBS show, Meet Corliss Archer, Sam was also in a number of movies in supporting roles playing opposite actors such as John Wayne and Gregory Peck. He also spent some thirty years in television, acting in dramas, comedies and commercials. There he was seen frequently on shows such as Gunsmoke, Dragnet, and Little House on the Prairie. Sam is survived by his wife of 35 years, Beverly Edwards, brother and fellow actor Jack Edwards, three stepchildren, Bill, Deborah, and Linda, plus five grandchildren through his marriage to Beverly. |

| Beginnings | ||||

|

Sam Edwards wasn't quite born in a trunk in the Princess Theatre, but he entered this world as part of the third generation of a show business family. Sam (rarely ever "Mr. Edwards") was born May 26, 1915, in Macon, Georgia. He can hardly recall his first time before an audience. While a babe in arms, he was carried on stage by his mother, famous actress Edna Park, in a play called Tess of the Storm Country. It would be a long time before he gave up acting, having evidently caught the fever in infancy.

Edna Lorraine Watson Nelson (b. 1892) was known up and down the east coast as Dainty Baby Edna, a name quite fitting for her four-foot, seven-inch stature. By the time Edna was a teenager, she had joined her own mother, Bonnie Brown Watson, as the smallest and youngest member of the Four Dancing Watsons, kicking her high-buttoned shoes as she pranced on the vaudeville circuit. She was married in 1910 at age 17 to fellow actor Samuel John Park of Indiana. They were shown living in Punxsatawney, Pennsylvania (home of the world's most famous groundhog) with his family in the 1910 Census, both listed as actors. Samuel was also the father of Florida M. Park born April 10, 1911 in Florida, and Sam George four years later while they couple was staying in Macon, Georgia. The tenuous relationship between the Parks did not last long after Sam's birth, and they divorced in mid 1916. Samuel J. Park was back in Indiana when the 1917 draft was taken, still listed as an actor but now a free agent. Sam did not even know who his birth father was until he met him once in the early 1940s in Hollywood. Two correspondences between them still exist.

Edna married Sam's stepfather (who he always considered his true father), actor Charles Ladson Edwards (7/22/1895), around 1917. Edwards was a life long resident of Macon where Sam had been born, and was listed in 1917 as a member of Edna's company. He changed his name (perhaps due to a conflict with another actor) to Jack L. Edwards, matching his father's given name, around 1919. In the marriage transaction, Sam gained a total of 11 aunts and uncles as Jack was the third of 12 children born to farmers Jack and Lizzie Edwards. Edna did continue to act for a while longer. She had been the leading lady for cowboy actor Tom Mix on a few occasions, and did some early films in the New York area. Her career in the movies ended abruptly one day when a director did not tell her that the railing on the ship she was filming on would break away when she leaned on it as the villain approached her. Even though they were ready and quickly snatched her from the water, she had suddenly had enough of that nonesense, and chose to become a full-time mother, never returning to the movies, but eventually moving to the stage and then radio. The family is not found in the January 1920 Census, very possibly because they were in transit when it was taken.

It should come as no surprise that Sam, his sister Florida, and his brother Jack Lawson Edwards Jr., (born in Florida in 1919), would all become involved in show business. One of Sam's earliest recollections of being on stage is one he would rather forget. The play was Why Men Leave Home with his mother playing the leading role of Miss Ketchum. Sam had to play the part of Miss Ketchum's daughter, but the lace panties he had to wear didn't fool everyone in the audience, and certainly didn't please little Sam. He also recalled the experience of surviving a hurricane during the time the family was living in St. Petersburg Florida, and the strange moments of being inside the eye as it passed over.

The couple and their children became the darlings of San Antonio, and their extended stay in San Antonio became semi-permanent for many years. And so it was that Sam, Florida and Jack spent their formative years in Texas surrounded by theatrical people. Sam vividly remembered when he would walk home from school some days and the habenero and jalepeno peppers were growing everywhere. He talked about just picking them off and eating them, often getting blisters on his lips, but still enjoying the experience. By the late 1920s, when talking pictures were quickly growing in popularity, dramatic stock and the remnants of vaudeville quickly waned. Note that Jack had continued to promote Edna by her married name under which she had gained her reputation, and would continue to do so until at least 1932. The family is shown in San Antonio in the 1930 Census living on West Craig street, with Jack Sr. as the manager of a movie theater. He would mix stage shows and presentations of Edna and the children with the latest movies that came through town. In that Census none of the other family members have an occupation listed, but that doesn't mean they were not working. There are advertisments from as early as 1930 showing Jack and Edna performing radio shows on WOAI, one of the earliest radio stations in Texas. This was the beginning of the family shift to the new medium. | ||||

| Early Radio Days | ||||

|

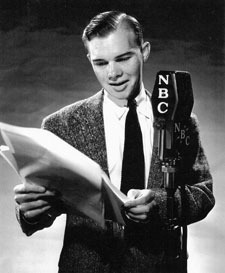

Around the time Sam became a teenager, he started singing at and often winning talent shows held at the downtown theaters. He proved to be so popular with the audiences, a combination of his voice and his boyish charm, that the managers asked him to stop showing up so someone else would have a chance to win. During the holidays, he sang Christmas carols over WOAI. While still in their teens, Sam and his brother Jack started contributing to the family income through their collective talents. With Edna writing the scripts and father Jack playing the adult male roles, the family spent nine months broadcasting The Adventures of Sonny and Buddy in San Antonio and Shreveport, Louisiana. This weekly program, one of the earliest serials ever broadcast on radio, was about two young boys who ran away from home and traveled with a medicine show. Every week the program featured Sam and Jack singing popular songs. On one very special occasion, the show was broadcast in Havana, Cuba, so Sam's grandmother Bonnie, who resided there at the time, could hear her grandson belt out Pagan Love Song. Jack Sr. was still managing the movie theater, and Sam bagged popcorn for patrons, sometimes taking in more money than the box office.

San Antonio Light, March 14, 1932 in "Around the Town:

If your household includes children and a radio you are bound to have listened to some of those juvenile-appeal programs advertising a breakfast food or something broadcast from KTSA at 7 each evening. A Trifled touched by the contagious enthusiasm kids have for the songs and conversations of Uncle John and Sonny and Buddy, you might have reflected very cynically that Uncle John probably never sees his two "nephews" outside the broadcasting studio. Well, you're wrong. He is not their uncle, he is their father. Sonny's real name is Jack Edwards Jr. and he is going to school out at Mark Twain junior school. Buddy's real name is Sam Edwards, and he attends the new Thomas Jefferson senior school. Everyone knows "Uncle John," their father, as Jack Edwards, actor and theater manager. The other night one of the boys got off on the wrong key on a song. Edwards made some remark about the piano being out of pitch and then they got started off on the right foot. Their daddy was proud of that. He said it showed they were real troupers; they didn't lose their heads. And, just to show you how much this sort of thing runs in the family, the mother, Edna Park of the stage, writes the continuity of the programs while the boys are at school. San Antonio Light, October 13, 1933 in "Around the Town:

Sonny and Buddy Edwards, the sons of Jack Edwards and Edna Park, are now in Shreveport, La., doing a [sic] adventure program over KTBS. Mrs. Edwards (Edna Park) is there with them, writing the continuity and dialogue for the programs, as she did her [sic] for several years. Edwards himself, just back from New York, says the kid[s] will be on NBC next year.

In 1933, the depression was well entrenched in the country, and radio and movies were the only viable and, for many, affordable forms of entertainment. In articles in the Express as early as 1931, Jack Sr. was referred to as a "former actor," and soon was known as the president of the Houston Street Association, a business collective named for the street on which the theater he managed stood. However, "former" may not have worked so well for him. It became evident that it was time for the family to move on to a location that had better resources and a growing distribution network if they were to continue in show business. The direction of the move was ultimately determined by the flip of a coin. Heads, it would be California, and tails, it would be New York. Fortunately for West Coast radio fans, and eventually those all across the country, the family packed up their 1926 Chrysler Imperial in early 1934 and headed west.

The trip took nearly a week, and the family arrived in San Diego with very little money.

In 1935, at the end of the Sonny and Buddy broadcasts, the family moved north to Hollywood. All five of the acting Edwards started free-lancing on radio programs like Calling All Cars, Those O'Malleys, The Union Oil Show and others. They also appeared in some B-movies produced by Monogram Pictures, one of the many film factories that tried to turn out a movie a week. One such film, possibly his earliest, was High Hat from 1937 produced by Imperial Pictures, and the only film in which Jack and Sam were credited with their stage names of Sonny and Buddy Edwards.

In mid 1941 Sam got his first of many jobs with the Walt Disney Studios. Many radio actors were utilized by the studio to add excitement and notoriety to their films.

| ||||

| We Interrupt This Broadcast | ||||

|

At the onset of World War II, Sam's radio career had started to soar, but he knew that it was only a matter of time before he would be called to serve his country. In early 1942, he had a pivotal role, although a fatal one, in Rubber Racketeers, a film about the dangers of buying black market tires during wartime. During the summer of 1942, Mr. Edwards spent a couple of months shooting a Saturday afternoon serial called Captain Midnight, playing the part of Chuck Ramsey, one of the Captain's loyal sidekicks, who could never seem to see the bad guys coming, or manage to hold on to his gun even when he did see them. The series was a continuation of a run it had on radio, albeit without Sam. After shooting the last of the 15 episodes, Sam stopped by a Navy recruiting station in Hollywood to check out his options, but decided to think it over before signing up. He finally did enlist in Los Angeles on July 25, 1942. The record shows him as an actor, single, without dependents. A few days later, after returning from San Francisco, where he was still appearing on Hawthorne House, he received his inevitable "greetings" from the Commander in Chief, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and found himself in the Army.

After three days at the Army Induction Station, Sam boarded a troop train headed for Sheppard Field, Texas, where he was assigned to the Army Air Corps, predecessor to the U.S. Air Force. Three days out, while having some chow at the Harvey House in Gallup, New Mexico, the soldier in training was told he was to return to Ft. McArthur in San Pedro, California, but he had no idea why. Sam was actually looking forward to being a part of the Army Air Corps and training to be a flyboy.

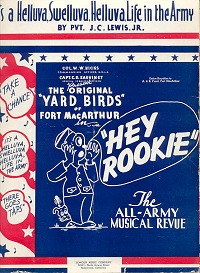

As the curtain went up on opening night of what was initially conceived as a two-week run, the composers were still finishing some of the musical arrangements and even lyrics. As Sam clearly recollected, the show was really rough that first night. The performers had been sleeping on cots backstage in a frantic effort to put the production together within such a compressed time frame. They had not even had a dress rehearsal, but the scant audience didn't seem to care. They loved everything about Hey Rookie. Even though not one ticket had been initially sold for the second night, word got around fast, and the house was about half filled at the opening curtain. By the third night, after reading glowing reviews in the newspapers that lavished praise on the show, the theater was nearly full to capacity. Hey Rookie was a smashing success that performed to standing room only houses for the next eight months.

With the war and the number of troops escalating, General Dwight D. Eisenhower called for more entertainers overseas, and the Hey Rookie show rang down its last curtain. The Special Services needed fresh entertainment in North Africa, and the nucleus of the cast and orchestra shipped out to Fort Meade, Maryland, then on to Africa. They had rearranged the set and logistics of the show so that it could be set up in the field in a matter of minutes. As the troupe vocalist, Sam's most popular songs were I'll Be Seeing You, Begin the Beguine, Sonny Boy (one of his favorites to the end) and It's a Helluva, Swelluva, Helluva, Life in the Army from the Hey Rookie show. The latter was also published in sheet music form, a rare find today.

After playing to more than two million troops in Africa, the group was doing what they assumed would be their last performance at the Algiers Opera House, but fate stepped in once again. In the audience that night were Generals Eisenhower and George Patton. The entertainers snapped to attention when both generals showed up back stage. Eisenhower said it was the first show he had attended since the war began and that he was there because the reputation of the performers preceded them. He told them, "You may not be pulling the trigger on a weapon, but the job you are doing is just as important, and you have my blessing. Officers like men who do their jobs well, and you do yours exceedingly well." So rather than being sent to a replacement depot, the performers were assigned to Patton's Fifth Army and sent to Naples, where they spent three months entertaining troops along the front lines.

Once again, the troupe was about to be disbanded and assigned to military duty, but General Ike stepped in once again and had them sent to the China-Burma-India Theater to continue with the show, given the morale benefits it had on troops elsewhere. When peace was declared, the group was in Chabua, India, where Sam lay in an Army hospital recovering from his third bout of malaria. He remembered vividly about their long train rides through jungles so dense that they constantly brushed the sides of the rail cars, and how the heat and mosquitoes often took their toll on the entertainers and other soldiers alike. After serving more than two years overseas, ultimately as a Buck Sergeant, Sam finally arrived back to civilian life in Hollywood, where Jack (who was not able serve due to physical limitations) and Florida had become popular radio performers. Jack had also continued some film work, appearing in such classics as a military short warning of the perils partaking of female professionals while on leave, and the classic Cross of Lorraine starring Gene Kelly. His radio and film work would also continue into the 1950s, sometimes intersecting with his older brother's career. | ||||

| Back Into the Radio | ||||

|

At this point, Sam felt he might have difficulty jump-starting his career after a three-year absence. His role in One Man's Family had understandably been written out. As Carlton Morse put it, there were too many babies and people in the cast, so Tracy Baker was shot down over Africa during the war, along with Sam's continuing role. However, good fortune smiled on him, and within days of arriving home, he was cast nearly concurrently in the radio soap Guiding Light with a rather convoluted story line, as well as Cavalcade of America with Lloyd Nolan. Jack had also been called for the part, but he had a conflict while doing another show (a common dilemma with the busier actors at that time) and sent Sam to fill in for him at the first reading. The show's producer, Jack Zoller, suggested that Sam was a better type for the part. Jack agreed and insisted that Sam be cast in the role, in spite of valiant protests on his part. It wasn't long before other producers were calling, and soon Sam was cast on Dr. Christian, Lux Radio Theatre, The Life of Riley, and many other post-war shows.

It was rare during these days that any radio actor supported themselves with but one role. So Sam kept busy, or, more accurately, was kept busy by other productions in Hollywood. Most of these were guest shots playing incidental characters for both comedy and dramatic series. His story is like that of many character actors, who sometimes did three gigs a day, sometimes two of them live, often at opposite ends of Hollywood Blvd., or even over the hill in the San Fernando Valley. While many shows were done live, the advent of audio tape in 1947 and better formulations for the large 16" transcription discs in 1948 shifted the balance to the more convenient schedule allowed by recording shows in advance. Another advantage, sometimes eschewed by the seasoned professionals, was that of editing out mistakes or changing dialogue after the fact. Sam rolled with the punches in any case, and accepted the challenges of live radio equally with those of doing multiple takes during recording sessions. Much of the time it was at the discretion of the producer as to which method would be used, but ultimately the control of the finished product that could be achieved with magnetic tape helped to make it the preferred medium for most dramas and some comedies by the early 1950s. In fact, some film actors or actresses (such as Joan Crawford) who appeared on radio insisted on appearing only on shows that produced edited transcriptions as they did not want to make an on-air error that could (in theory) harm their career.

Dragnet was also a boon to Sam, but it could have been more difficult for him to work with Jack Webb if not for the latter's sense of humor (he really did have one). It seems that in the late 1930s, Webb had auditioned for a part on the Five Edwards show in San Francisco. He was ultimately turned down because, as it was later described, he sounded too much like Joe Friday. So when Sam was first hired for the radio Dragnet, he apologized in that first awkward moment for the rejection of a decade before, likely his father's decision. Reportedly, Webb told Sam "That's all right. I probably sounded too much like Joe Friday anyhow." Go figure. He would work with Webb in Hollywood until the mid 1970s. Although Sam found that he preferred California, where the majority of the radio action was, he spent three productive months during this period in the Big Apple (NYC) doing Mr. President with Edward Arnold. In any case, the bulk of Sam's estimated 8,000-plus radio episodes and appearances occurred during this period from 1946 to as late as 1962. | ||||

| The Transition to the Big Screen | ||||

|

Although Sam was no stranger to film, having appeared in at least two features plus the Captain Midnight serial before WWII, his primary milieu up through the late 1940s had been radio.

A very dramatic appearance was well conceived in the film version of Gangbusters in 1954, in which Sam's character, Wayne Long, commits robbery and murder in order to impress an inmate idol of his, John Omar Pinson (based on a true story). He reprised a similar tough guy role in the 1958 production Revolt in the Big House, a movie that even lots of good acting had trouble saving. However, a role is a role, and if you play it well, it can be the highlight of even the film no-more genre. He also had parts in the 1954 thriller Witness to Murder with Barbara Stanwyck, and the predictable gang flick Guns Don't Argue in 1957. All of this and fulfilling his many radio continuing obligations as well! What else could enter the mix to keep Sam busier? | ||||

| In Comes Television | ||||

|

It turns out that the element of success and further continuing employment for Sam would be television, where he was kept busy for the better part of three decades.

Sam often appeared on several early television series that had their roots in radio. These include The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The Burns and Allen Show, Death Valley Days, Gangbusters (in addition to the film), The Jack Benny Show, and long-running The Red Skelton Show. He would appear on the Skelton series many times throughout the 1960s, including one episode with fellow actor John Wayne. It is clear that many of the television shows of the late 1950s to mid 1960s were a reflection of radio shows, or actual visual incarnations of these shows, so radio actors that had the right look were certainly desired during this transition. Shows like General Electric Theater and You Are There on CBS did their best to integrate radio scripts (from radio script-writers) into a palatable visual medium, often on a soundstage. For the former, he was Bob Cratchit in a Jimmy Stewart-produced version of A Christmas Carol set in the old west. On radio he had played both Bob and Fred, nephew to Howard McNear's Eben (Scrooge) character. You are There reenacted historical events as if news cameras were there covering it, and Sam made a pair of appearances on this series. He also landed a part as a bellboy on I Love Lucy during Lucy and Ricky Ricardo's trip to England, and on to Europe.

| ||||

| The Multi-tasking Actor | ||||

|

By this time it got to the point where this actor who was not particularly famous, not a big star, but well regarded and easily recognized, woke up many mornings possibly wondering if it was cameras, studio lights or microphones that he would face that day; sometimes it was all three.

Gunsmoke started on the radio in 1952. It was hardly the first western, as such radio shows went back to the late 1920s. Sam had previously been featured in many episodes of Tales of the Texas Rangers and western stories on other shows. However, Gunsmoke simply had the right team working on the right scripts using the right actors, great music score, great production, and consistent quality. Sam did no less than 100 episodes of the radio series right up through 1961 when it was cancelled in favor of television. Frequent use of him as either a guest star or background character helped him to be cast in future westerns both on television and radio, and occasionally film. Roles on similar radio series, using some of the same team members from Gunsmoke, included various parts on The Six Shooter starring Jimmy Stewart, and as a regular cast member on Fort Laramie, which starred Raymond Burr. There was also the short-lived Luke Slaughter of Tombstone and the highly popular Have Gun, Will Travel, which ended only slightly before Gunsmoke.

A character actor can't live on the old west alone, much less playing juveniles into his 40s. So exercising versatility, Sam also landed roles on Romance (not quite a show about Don Juans, given some of the plot lines), a recreation of Brave New World on CBS Radio Workshop, and many appearances on a Salvation Army produced show, Heartbeat Theatre, with limited production but effective human interest scripts. But other than the westerns and Heartbeat Theatre, most of the regular radio shows were superceded by television versions of the same, often using the same scripts, or they simply made way for disc jockeys, news and talk radio. By 1962, radio drama was floundering. It would come back for a time, but not during the 1960s.

Then the TV westerns discovered Sam. Well, sort of. Actually, he had been doing Gunsmoke on radio with Bill Conrad and Parley Baer pretty much since its inception (he worked with them on many other series as well, considering them life-long friends). But it's easier to play a cowboy on the radio than on the screen, as one might realize if picturing the extremely talented but somewhat oversized Conrad in the role that James Arness played on television. Even though it may be plausible historically that not all U.S. Marshalls were tall and svelte, for TV viewers and especially for advertisers, a certain "look" was expected. For Sam, this look was evident as soon as he put on a cowboy hat for Chester's Hanging during the first season of Gunsmoke on television. They used him often throughout the entire run, though often as a desk clerk. Sam just had that kind of desk clerk/telegraph guy look, because he would often play the same type of role on other westerns as well, including a recurring role as such on The Virginian. Still, he did make a convincing cowhand.

As noted, many of the early television shows were either based on successful radio shows or followed their formula, using their writers as well. However, the nature of TV changed as directors and producers discovered the visual merits of car chases, exciting locations, and other things that were more difficult to convey on the radio. Some also believe that TV shows sucked the imagination out of people since the shows presented all the visualizations for you, something that the "Theatre of the Mind" worked so hard on. One could listen to a radio show on which the characters are on a ship during stormy seas and, depending on the acting and the sound effects, actually get seasick listening. Television removed many of the visual elements of the "mind's eye," replacing them with a director's vision instead. Both were valid points of view, and remain part of a larger debate to this day. As for Sam, he supported both and never bit the hand that fed him. Many of his mid 1950s to mid 1960s appearances were indeed in shows that were more or less radio on the screen, but color television and the public's demand for something different altered the look and feel of television in the mid to late 1960s, further separating it from radio, and further overtaking it as well. Although radio series were, for the most part, history by the mid 1960s (some of Sam's last appearances before the revival were in 1964), many nostalgic people held on to it through their memories and recordings until the first revival in the mid 1970s. | ||||

| Animated Antics | ||||

|

It was a common practice for studios to hire radio voice talent for cartoons, as such actors were a known quantity. As a result, Disney, Warner Brothers, MGM, and Hannah Barbera kept a variety of actors well-employed putting words into the mouth of colorful drawings projected onto the screen. Among these actors that were better known to the industry were Jim Backus, Dawes Butler, Stan Freberg, Janet Waldo, June Foray, Jane Webb Edwards (Sam's sister-in-law), Pinto Colvig, Sterling Holloway, Clarence "Ducky" Nash, Hal Smith, and the ubiquitous "Man of a Thousand Voices" (I have only counted 843), Mel Blanc.

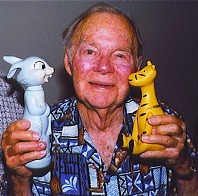

For PBS, Sam did frequent voice work on a bi-lingual series called Viva Allegra in the mid to late 1970s. He also recorded for some educational filmstrip series produced by Silver Burdett, including one about the old west and the pioneers. Other animated series included a run near the end of the popular Jonny Quest series of the early 1960s. The 1970s brought Wait Till Your Father Gets Home and These Are The Days. However, in that period between The Flintstones and The Simpsons, it was difficult to sustain interest in a prime-time animated series, so they ultimately did not last long. One final animated series was not that far off from his first major run, and was titled Rickety Rocket, where he provided a number of character voices. There are many more uncredited voiceovers that Sam was responsible for, including some looping work for James Dean in East of Eden, and commercials for both radio and television. Sam even contributed to the voices of the Oompa Loompas in the 1971 film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. As long as the performer was compensated, such work commonly existed without public recognition, but an agent who wanted to find a particular performer (which for Sam was fortunately a frequent occurrence) would have had little trouble since the studios kept good records. | ||||

| A Flurry of Film Activity | ||||

The following year and new decade, 1970, brought a great performance in any otherwise questionable film. It's not that the actors hired for Suppose They Gave a War and Nobody Came were bad. After all, there were Tony Curtis, Brian Keith, Ernest Borgnine, Don Ameche, Suzanne Pleshette and many other familiar faces. It suffered from an ambiguously motivated plot, which was protesting the war in Vietnam in some regard by focusing on state-side malaise and tensions between an Army base and the local citizenry. As a deputy sheriff who is tasked with stopping a tank early in the morning with only a gun and wits, Sam provides one of the more entertaining moments of the film as he looks up at the car-crushing behemoth on a vacant desert highway and asks, "What the hell are you guys doin' out here this time of the morning?" (Click here to listen.) Was that really the point? That's the comedy of it. His agent nonetheless rewarded him with a part in The Cheyenne Social Club with Jimmy Stewart that same year. We have evidence of more feature film appearances from this time via call sheets and residuals, but given his popularity as a voice actor, his appearances in such films as Dirty Harry, Bullit and Magnum Force may well have been through looping over other actors only. Updates will be posted as we research them for the full biography.

Sam's work in television also translated into a new genre of movie, the made-for-TV film (at one time called "Movie of the Week"), which originated in 1971 with Steven Spielberg's classic thriller Duel. Some had been done before that, but the TV film factory has often been traced to this early ABC presentation. Although Sam did appear in selected features of the 1970s, the bulk of his screen work was on television. Some of these, such as O'Hara, United States Treasury: Operation Cobra or Chase, were pilots for or extensions of established series. Others were TV versions of larger scale disaster films, such as 1974's Hurricane Hunters. Other familiar titles are The New Daughters of Joshua Cabe and Mark Twain: Beneath the Laughter. One interesting television movie that Sam acted in was called The Incredible Rocky Mountain Race featuring a whimsical story about a race between Mark Twain (Christopher Connely) and Mike Fink (Forrest Tucker) as narrated by the elder Mr. Clemens. Another interesting role was in a trilogy of short films gathered under the general title Moviola, his appearance specifically in The Scarlett O'Hara War, a story of the casting of this coveted part for the 1939 feature Gone With the Wind. All of these demonstrated the evolution of television into its own medium in a distinct separation from its ancestors, radio and feature films.

The 1970s also brought some more work from Sam's long-time friends at Disney. The first was in Scandalous John, a sort of western story about a cranky rancher dealing with his rights. Another was a seen-but-not-heard role on a feature originally made for television but released theatrically, Escape to Witch Mountain, still a popular Disney classic. His most extensive role was also a somewhat dangerous one; an appearance in Flight of the Grey Wolf, also a TV feature repackaged for the theaters. He had to go on location to Northern California for this film, and was required to ride a horse. Things were compounded by the movie's star(s), trained but still not always predictable grey wolves. As a cost-cutting measure, Disney hired a wrangler but not his horses, due to the cost of transporting them to the location. So Sam ended up with a horse that had little acting experience and even worse manners and temperament. As a result, something spooked the reluctant beast and Sam was injured falling off of it while having a foot caught in the stirrup. He finished the shoot with no further serious episodes, but a painful injury, and never mounted a horse after that incident. Radio had sound effects guys to take care of these problems aurally. No wonder it was his favorite medium!

For those who liked the more quirky cult series, Jack Webb reused Sam on his short-lived Project U.F.O., he had a notable appearance on Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and even two turns on The New Adventures of Wonder Woman. Fans of the outstanding Then Came Bronson will know him from one of the more controversial episodes of that show dealing with a nude painting on a barn, and the mistaken identities of who the female subject was. Since Gunsmoke finally took a bow in 1974, westerns were rarely in vogue for quite some time after that. The closest thing to a western series as the 1980s approached involved Sam's final appearances on screen, a continuing role on the long-running Little House on the Prairie. Here he played a couple of different characters, including the town's postman in an early appearance, and Mr. Anderson the Walnut Grove banker throughout the remaining seasons of the series until 1983.

Aside from Little House, his last two TV appearances show Sam at his funniest. On Happy Days he is a country doctor tending to Fonzie (Henry Winkler) who got shot in "the part that goes over the fence last." And one unlikely but fun one-day role is among the most difficult to locate, but reportedly one of his most hysterical portrayals. It was as a drunken justice of the peace on the daytime drama The Young and the Restless. There was one more "almost" at this time as he auditioned for and was second-pick for the part of the cook in City Slickers, which was ironically enough filmed near his new home in Durango, Colorado, where he had moved by this time. In any case, commuting to and from Colorado, or finding jobs during his visits to Los Angeles became cumbersome, and Sam made the decision to retire from television and film after a successful career in both spanning collectively over 40 years.

| ||||

|

For more linked listings of movie and television appearances that Sam Edwards made, you may follow the link below to his page on the Internet Movie Database.

| ||||

| The Private Side of the Public Guy | ||||

|

Up to this point we have focused on Sam's lengthy career in the public eye and ear. However, there are many extraordinary facets of Sam in his personal life that are worth conveying to the world for a more complete picture of the accomplishments and legacy that he has left behind. They are full of the same level of great anecdotes of his personal life as well, and many will be saved for the print version of his biography. However, some of it will be presented here from the perspective of his recollections, that of his wife of 35 years, and from his three stepchildren, or more correctly, self-adoptive children. As his stepson or son, I will do my best to represent all of these views as I have heard them frequently from others, and as I experienced them myself, and will thank you for your acceptance of my indulgence in this regard.

Sam was what some often jokingly referred to as a "confirmed bachelor," in spite of three engagements over the years, and someone who was content in his status as a single person Given how active he was in the entertainment business, he was possibly too busy at times to sustain a serious relationship. He usually kept many details of whom he was dating through the 1940s to the mid-1960s to himself, and we will not drop names here, but some of them include fairly well-known actresses. Radio fanzines often linked him, as they did most well-known actors and actresses, with somebody now and then, but it was largely publicity, as it still is today. Sam bought a couple of homes in Studio City, California, in 1949, and actually held on to one of those properties until 1980. It was in the south end of the growing San Fernando Valley, centrally located to the movie and television studios (thus the name), as well as radio production facilities over the hill in Hollywood. At one point, Sam also owned and lived in the house next-door to his second Studio City residence, as explained later.

Know that Sam was also dedicated to his family as well. His brother Jack and sister-in-law Jane Webb lived just a few blocks away for a very long time, and his sister Florida, who by the 1960s was no longer working regularly in show business, also lived near by at times. Jack Edwards Senior, long retired from show business, had died, possibly in 1959. Sam's actress mother Edna was cared for by Sam and his siblings, living at times with Sam in Studio City until her death on June 5, 1967. I personally went with him on a few visits to her grave at the famous Hollywood cemetery.

Then one day things changed drastically for the "confirmed bachelor." Sam was exercising one of his favorite pastimes, the game of tennis, in a celebrity tennis tournament in in the spring of 1966. Also in attendedance were his good friend and neighbor down the street, actor Bill Erwin (Home Alone 1/2 and Somewhere in Time as Arthur) and Bill's wife (the late) Fran Erwin. Fran worked with newly-divorced Beverly Motley at the Valley News and Green Sheet, a paper that literally had a green front page, and was working to be a serious competitor to the Los Angeles Times. Both Fran and Beverly were covering the event for the publication. It was there that Sam was introduced to his future wife by Bill and Fran, and that's where the stories really begin. During the next few years, it would often come in handy that Sam was an actor by trade, because he would have to take on a number of new roles that required great adaptation.

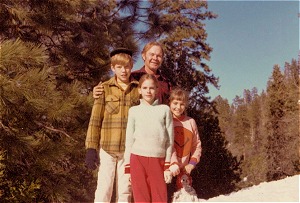

Let us iterate one of his first meetings with his future stepchildren, and his good humor dealing with them. Bill was 7, Deborah 5 and Linda 4 at the time. On the first occasion that he appeared at the door for a date, one of the three of us (no names here, and we frankly can't seem to agree on who) unceremoniously announced, "Mom, whatever you're going out with is at the door!" He didn't run. During an early date the topic of our favorite show came up. It happened to be Rod Rocket. It seems that as a result of this cartoon that I watched religiously, and my sisters when they happened to be around, that I had learned to count from 1 to 10, or more rightly from 10 to 1, something that she was trying to correct. She had a problem with Rod Rocket. That's when Sam announced, "Well, I'm Rod Rocket," with good humor, of course. He didn't run.

Then there was the move toward a serious relationship that was a true test of character of Sam, and which I will fondly share as a humorous but important memory. In order to progress in the serious relationship, Beverly, showing a touch of class that is rarely seen in this decade, chose one last date with her current suitor (whom we called "Mister Ed" but will otherwise remain nameless) in order to politely announce her intentions. HOWEVER, she could not find a sitter. I don't believe it was the children that compounded the problem. I just think it was the wrong night to locate a starving teenager or responsible adult with idle time. SO! As a last resort she called... Yup! Sam. He chivalrously agreed to make the 20 mile trek under the circumstances and watch after us while she finished up business with Mister Ed. Somehow, he became convinced (not of his doing, I'm sure) that we were all supposed to take a bath at the same time (c'mon, we were little; this still happens elsewhere). That was likely the highlight of his evening. In any event, when Beverly came back, Sam was partially unconscious on the couch while we were happily in bed, and things were fine until she observed the ceiling of the bathroom, which looked like the canopy of a rain forest. Don't know if he got a tip for enduring that, but he got the brass ring for sure from all of us. And he didn't run.

At that time, we lived in Northridge (sound familiar) at the north end of the San Fernando Valley. My mother accepted a job in 1970 at the world famous Beverly Hills Hotel as their public relations director, which was exciting in that she directly handled the visits of many notable personalities, but also meant an extended commute on the increasingly congested freeways and roads of Southern California. That would change as a result of a momentous event. I remember that on February 8, 1971, that Sam accompanied me to my last Cub Scout Blue and Gold Dinner, which was held at the local Shakey's Pizza Parlor. That was not all that was "Shakin'." The following morning around 5:59 a.m. I awoke to the noise of virtually every dog and cat in the neighborhood sounding off about something. It was eerie to say the least, particularly since it was still dark. I drifted off a little, but at 6:01 the earth unleashed itself in nearby Sylmar. The end result was a 6.7 quake that changed the lives of many in the northern San Fernando Valley. Sam managed to keep us all calm, despite the trauma that we and our house had experienced. The toilet covers had jumped to the floor, and the refrigerator and piano moved quite a distance as well. The kitchen was nearly covered with broken glass and assorted liquids. Parts of the ceiling had come off, and there were cracks in most of the wall joints. Then the reports of the potential of the nearby reservoir dam breaching caused us to temporarily relocate to Orange County for a few days, even though we were not directly in the path. It should be noted that for the rest of our time in that house, it never stopped moving. The place was constantly creaking and swaying just a bit, a very eerie sensation. Sam did what he could to put things back together, but in mid April an aftershock that was centered more or less directly under our house shook it up and down violently, as opposed to the lateral motion of the previous quake, and that codified things. Turns out that even though his Studio City house was not currently available due to the lease in place, the house next door was up for sale. Since the south end of the San Fernando Valley is less rock and more sand, it was less susceptible to the constant and sometimes horrendous shaking that would continue for the next few years. And so, it was that we moved into the heart of motion picture activity, and were now on Sam's turf, an exciting change for us all.

As evidence above shows, Sam was extremely busy in his work in the 1970s, while we were making the rounds of junior high and high school with many other kids of actors, producers, composers, lawyers, and other Hollywood types. In reality, Beverly had as much access to high-powered entertainers as he did, being responsible for many of the details surrounding their stay at the famed Pink Palace of Beverly Hills. I don't think it ever fazed Sam that while we could watch him on screen on the Red Skelton Comedy Hour with John Wayne, or on something exciting like Mission: Impossible!, Beverly would bring home stories about Liz Taylor or even autographs of celebrities like John Denver or Paul McCartney. We were three kids in the realm of "cool" for the most part, but having been ushered into this so naturally it simply seemed just a little extraordinary at the time. We also had many of his actor friends attending parties regularly at our home, which was always great fun. Since Beverly usually arranged the details of these parties, we did not always know who had invited which guest, but since everybody had a good time and got along, that is incidental now. In retrospect, having viewed Sam's career backward from the end of his life to his early days while composing this piece, it turns out that he simply did not always let on to us about that extraordinary career. This shows the wonderful non-competitive part of his nature, the rest of which he applied most appropriately

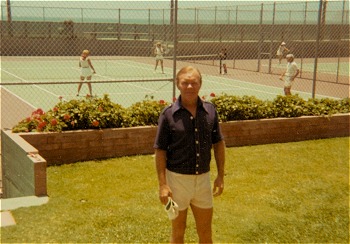

When Beverly had the rare day off, she and Sam sometimes drove to Newport Beach where she would shop and he would play tennis at a popular club there. It was managed by Glenn Turnbull, an old Army buddy of Sam's. One day Glenn set Sam up to rally with a young girl or 12 or 13, who needed a match for the experience and training. Sam went easy on her for perhaps a serve or two, but quickly learned the potential of young Chris Evert, a name he would not forget. To the end of his life he followed tennis whenever he could, his favorites being Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, the latter of which he had the thrill of attending in 1982.

What kind of car does an actor drive? We knew many of them, and unless they were the ostentatious stars you saw in the tabloids or omnipresent on the screen, they usually drove just a car. In fact, some big names didn't necessarily maintain a status for all that long which allowed them such a luxury. At one point in the 1970s, the late Donald O'Connor, perhaps the driving force behind the most memorable scenes in Singing In the Rain with Gene Kelly, was not working so much, and was certainly down on his luck. In fact, he was near the point of a loan default that would have resulted in a repossession of his car. As a member of the AFTRA Credit Union finance committee, Sam requested that O'Connor be given some time to get back on his feet which allowed him to keep the car. It was not a big effort on Sam's part given his generosity, but deeply appreciated by O'Connor, who did get back to work enough to justify the faith in him. Even at the end of his life, the entertaining comic dancer was overwhelmed at the renewed interest in his work of the 1950s, so perhaps he simply underrated himself.

Back to the question above. Sam had kids and a wife, so regardless of what he drove before, it was usually a big gas guzzler that dominated our driveway or the street. To compound things, Beverly was starting to migrate into a career in the recreational vehicle writing and editing business, so we had trailers that grew in size over the 1970s, requiring larger cars to pull them. But he still did indulge. While you may think many actors would go for a Rolls Royce or a Jaguar (Dean Martin had one with the license plate DRUNKEE), or the more powerful Shelby-ized Fords or foreign sports cars, Sam was content with a 1968 Camaro fastback for many years, followed by a 1969 MGB hardtop. Imagine, if you know such a car, five people crowding into it (it was done) for a casual trip to the ice cream parlor. But it was fun, so who cares. He was just plain folk, and yet extraordinary in that regard. To add some perspective to true coolness, the MGB was a manual transmission model (I don't think they made anything else). Two of the actors who played James Bond no less admitted that they couldn't even drive a car with stick shift, which of course includes various incarnations of the Aston Martins. Therefore, Sam could go where James Bond could not! Sadly, the MGB had to go when they moved to Colorado, but he had many fond memories of driving it, as did we in riding in it.

The moment of most meaning to me in regard to the MGB was the night, after I had been licensed a mere seven months, that he offered the precious yellow speedster to me for my prom (held at the now defunct Cocoanut Grove in LA). This was a show of character that had, perhaps, a bit of personal history going back to his high school prom and the incident with his father and the "borrowed" car. I was both excited and nervous about the opportunity to drive his precious car (I later owned an MGB ragtop of my own), and the gesture had immense meaning. It had been enough that I was allowed to put in the cassette deck stereo and ride in the thing once in a while. It made that night very memorable.

Sam set an example for each of us in our lives, and together with Beverly, allowed us to choose our path to independence with sometimes-unseen guidance. He was rarely judgmental of us (although there were a few actors he certainly had strong opinions about) and found ways of rationalizing the better way to do things without trashing the way we wanted to do something. To honor this, each of us had our names legally changed when we could do so. In a sense, while he did not directly adopt us, it was clear all along that we adopted him. There is power in that. Again, while his long career speaks a lot about the type of person he was, the personal side of Sam (and there are hundreds of stories that will be told someday soon) and the impact he had on all who knew him in that regard, is the most important part of his legacy. The past few paragraphs just touch on the surface of that, but they hopefully provide a glimpse of the quality of human being you have been reading about.

| ||||

| Back To Radio - The Final Episodes | ||||

Sam died peacefully in Durango on July 28 following a brief myocardial infarction that exposed a hole in his heart, some 12 years after bypass surgery. He was surrounded by his immediate and extended family and friends during his last three days, and as always, with much love. Now it is we that are left with a hole in our hearts, but it will forever be filled with wonderful memories of this man who was incapable of leaving behind a memory of any other kind. Thank you, Sam.

| ||||

|

Beverly Ann Edwards (loving wife - dec. 5/2019)

Rozella Scroggs Williams (sister-in-law - dec 9/2009) Jack Edwards (dec. 9/2008) and Jane Webb Edwards (dec. 3/2010) (brother and sister-in-law) Alan Edwards (nephew) Steven Monroe (nephew) William G. Edwards (stepson) Joanna S. Edwards (first daughter-in-law) Pamela L. Edwards (second daughter-in-law) Amber Quiring Bowden (dec 1/2016), Alexander Samuel and Zachary Paul Edwards (grandchildren) Patric, Marcia and Kelsey Pederson (step-grandchildren) Deborah D. (Edwards) Billings (stepdaughter) Todd Billings (son-in-law) Sarah E. Rolland (granddaughter) Linda E. (Edwards) Langner (stepdaughter) John B. Cameron (first son-in-law) Eric Langner (second son-in-law - dec. 1/2020) Gordon B. Cameron (grandson) |

|

Additional movies and recordings in which Sam Edwards appears are available from other merchants through these links: |

|

The Best of George Pal (Little Broadcast-Complete) The Sun Sets at Dawn Guns Don't Argue |

| More Titles Added As They Become Available |

|

|

Site Map |

About Bill |

Bill's Biography |

Powered by iPowerWeb |

Contact Bill |

Frequently Asked Questions | | Ragtime MIDI/Covers | Ragtime Resources | Ragtime Links | Ragtime Recordings | Ragtime Nostalgia | |