Axel W. Christensen was an important figure in ragtime, not so much as a composer but as a promoter, trying to get the concepts of the music into the hands of the average pianist while making a nice profit at the same time. He was born to Danish immigrants Charles Christian Christensen and his bride Mary Anderson (sometimes shown as Larsen [1]), in Chicago, Illinois, a decade after the great fire that had leveled the city. Axel was one of seven siblings, of which three other boys and one girl survived to adulthood. They included Otto Richard (12/22/1882), Ingebord (3/18/1885), Charles Werner (1/24/1887) and Norman Victor (10/27/1891).

Axel had a typical musical upbringing that included piano lessons and harmony and theory. Contemporary reports described him as only average in his ability. There was reportedly an incident in his mid-teens in which after playing marches and some forms of classical music at a party he was shown up by a much better pianist playing early cakewalks or ragtime, something that the females reacted to in a very positive way. This evidently affected him deeply, and it was then that he became passionately interested in popular piano styles, including ragtime. By 1900 he was still only peripherally involved with music, as the census shows him working in mechanical engineering of some kind, the same field his father was in.

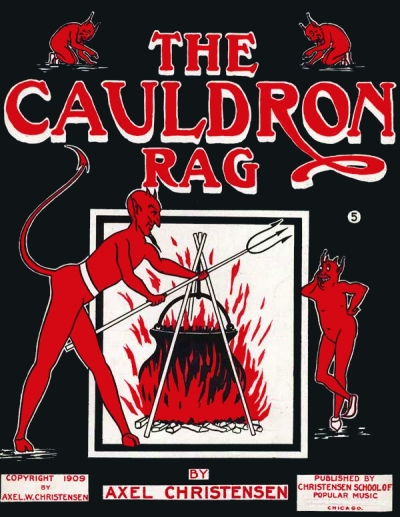

The young entrepreneur finally managed to compose and publish a rag in 1902, The Ragtime Wedding March (Apologies to Mendelssohn). The main point of this piece was to prove that virtually anything could be syncopated into a ragtime style, a catalyst for what was to come in his career. Determined to make good with his musical education and passion, Christensen opened his first ragtime instruction school in Chicago's Fine Arts building in 1903 with the promise of "Ragtime Taught in Ten Lessons." He had developed a curriculum that consisted of exercises in various syncopated patterns on easy melodies. His goal, although not overtly stated, was to teach the person not so much how to play a piano rag, but how to rag any music that they encountered or already knew. This was akin to turning around his own bad teenage experience into something positive - taking the 98-pound weakling pianist and making them popular with syncopated muscles. With good advertising and positive results, he was able to grow the business fairly steadily. Axel soon married Reine Annette Swanson in September of 1903, and she would eventually become materially involved in the burgeoning business. They soon established Christensen's headquarters in the Kimball Building.

Business reached a point of saturation in the Chicago area by 1908 with four school branches in various parts of the city. However, Christensen had been selling his books by mail order and in selected music stores in an effort to get to people outside of his Midwest radius.  The first of these was published The first of these was published in 1904, Christensen’s System of Rag-Time Instruction for Piano, followed by a similar entry in 1905, then in 1906 by Christensen's Instruction Book Number 1 for Rag-Time Piano Playing, the very title forecasting a series of such books. The basic course was updated at least five times during the ragtime era. Many of the exercises could be equated to a syncopated version of the famous C.L. Hanon exercises, repeating a syncopated pattern up and down the scale. Other focused courses also soon appeared in print, including a course on playing for vaudeville, a fairly lucrative profession at that time. Going beyond how to play, these books also outlined how to build up a well-paced set of anywhere from 20 minutes to an entire evening concert, important lessons for an entertainer to know in order to engage an audience.

The first of these was published The first of these was published in 1904, Christensen’s System of Rag-Time Instruction for Piano, followed by a similar entry in 1905, then in 1906 by Christensen's Instruction Book Number 1 for Rag-Time Piano Playing, the very title forecasting a series of such books. The basic course was updated at least five times during the ragtime era. Many of the exercises could be equated to a syncopated version of the famous C.L. Hanon exercises, repeating a syncopated pattern up and down the scale. Other focused courses also soon appeared in print, including a course on playing for vaudeville, a fairly lucrative profession at that time. Going beyond how to play, these books also outlined how to build up a well-paced set of anywhere from 20 minutes to an entire evening concert, important lessons for an entertainer to know in order to engage an audience.

The first of these was published The first of these was published in 1904, Christensen’s System of Rag-Time Instruction for Piano, followed by a similar entry in 1905, then in 1906 by Christensen's Instruction Book Number 1 for Rag-Time Piano Playing, the very title forecasting a series of such books. The basic course was updated at least five times during the ragtime era. Many of the exercises could be equated to a syncopated version of the famous C.L. Hanon exercises, repeating a syncopated pattern up and down the scale. Other focused courses also soon appeared in print, including a course on playing for vaudeville, a fairly lucrative profession at that time. Going beyond how to play, these books also outlined how to build up a well-paced set of anywhere from 20 minutes to an entire evening concert, important lessons for an entertainer to know in order to engage an audience.

The first of these was published The first of these was published in 1904, Christensen’s System of Rag-Time Instruction for Piano, followed by a similar entry in 1905, then in 1906 by Christensen's Instruction Book Number 1 for Rag-Time Piano Playing, the very title forecasting a series of such books. The basic course was updated at least five times during the ragtime era. Many of the exercises could be equated to a syncopated version of the famous C.L. Hanon exercises, repeating a syncopated pattern up and down the scale. Other focused courses also soon appeared in print, including a course on playing for vaudeville, a fairly lucrative profession at that time. Going beyond how to play, these books also outlined how to build up a well-paced set of anywhere from 20 minutes to an entire evening concert, important lessons for an entertainer to know in order to engage an audience.Axel was finally confident enough in the strength of his teaching methodology, which was frequently updated to include new styles as they came along, and opened a branch of his school in San Francisco in late 1908. The results encouraged him to expand to Cincinnati by 1910, and even Saint Louis, a hotbed of ragtime activity for a decade by that time. He also expanded his personal repertoire of compositions with a number of fine rags and songs over the next few years. In July 1910 the Christensens were shown living in a relatively nice area of Chicago with their recently-arrived only son, Carle Alexander, born July 27, 1909. They also had a live-in servant, so the publishing and teaching enterprise was paying off fairly well by then. He listed himself as a proprietor of music schools.

By 1910 Christensen was truly the Czar of Ragtime, a title which would stay with him for many years and that he used often in Vaudeville. In 1915, utilizing his passion for rearranging older tunes with syncopation, Axel released a series of these arrangements that were included in some of his courses and sold separately as well. His educational reach would eventually extend to 25 different cities by 1918, near the end of the ragtime era. Axel's 1918 draft record shows him still in Chicago as the owner and manager of the Christensen School of Popular Music.

In May 1918 in Melody Magazine, Christensen wrote a provocative article titled Can Ragtime Be Suppressed which extolled the virtues of the genre, and made clear that those who would try to prevent its continuation would ultimately fail in their endeavors due to the public thirst for more ragtime. While its origin was only a mere two decades in the past, he postulated on the mystery of that very genesis:

Many writers have endeavored to trace ragtime down to its origin, but there are almost as many opinions as to where ragtime had its source as there are writers on the subject. Ever since there has been such a thing as ragtime, there have been people who would tell you that ragtime was on the decline, and that it would soon be a thing of the past. Twelve or thirteen years ago a well-known music publisher told me in all seriousness to devote my efforts to something besides ragtime, because the knell of ragtime had been sounded; it had run itself to death and the publishers would soon stop printing it altogether. He sagely told me that if I had only gone into business a few years previous I might have made something out of it, but there was no longer any hope. That was twelve years ago and ragtime is now stronger than ever.

The truth is that it was on the way out, and the Christensen schools would have to adapt in order to follow the national musical trend to jazz.

It was reported in They All Played Ragtime that some 200,000 students had registered nationally with the schools by 1923. A 1923 edition of the Music Trade Review noted that Christensen had ninety-two branches around the country. Totals would eventually rise to 350,000 by the onset of the Great Depression, with another 200,000 by 1935, although the latter figure can likely be disputed given the economic climate. In any case, the school was likely responsible for a great many ragtime pianists that ranged from hobbyists to small town heroes, many of them perhaps playing either in vaudeville or for movie houses of the era.

Much of the success of his program, beyond the frequently updated exercises and examples, was his willingness to trust other teachers to follow the program and succeed as he had with it. Many of them also had careers as performers or composers. Among those who are known are Robert Marine from New York, Bernard Brin from Seattle, Marcella Henry from Chicago and Edward J. Mellinger from Saint Louis. It has been noted that at times 500 or more students would attend recitals at Mellinger's Saint Louis branch, and some of them became large celebrations of playing with student/teacher duets, trios, and perhaps even more, creating good press for Christensen.

Much of the success of his program, beyond the frequently updated exercises and examples, was his willingness to trust other teachers to follow the program and succeed as he had with it. Many of them also had careers as performers or composers. Among those who are known are Robert Marine from New York, Bernard Brin from Seattle, Marcella Henry from Chicago and Edward J. Mellinger from Saint Louis. It has been noted that at times 500 or more students would attend recitals at Mellinger's Saint Louis branch, and some of them became large celebrations of playing with student/teacher duets, trios, and perhaps even more, creating good press for Christensen.In addition to running this enterprise, Axel continued to write rags at this time, sometimes published separately but more often included in the courses. While not quite of the same quality as some of the better selling pieces of the time, they were still carefully crafted and accessible to his students. In 1912 he reportedly became one of the first artists to record "hand-played" piano rolls for the QRS company, a claim later contradicted by ads for another company saying he had not recorded for anybody else before 1923. Nonetheless, the QRS rolls state that each piece was "Played by the Composer." Christensen also published selected rags by other composers, favoring those who taught for them.

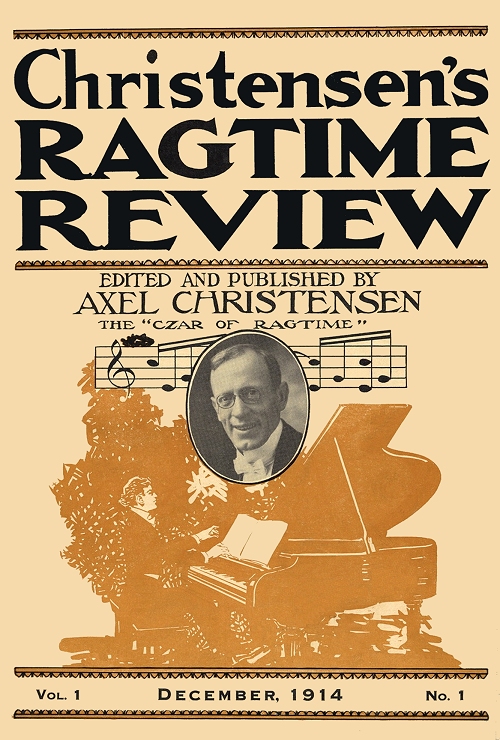

Another great promotional tool was his monthly Ragtime Review magazine which ran from December 1914 to late 1918, and included tricks and tips, humorous stories, articles on performers, composition reviews and reprints of rags by many publishers who licensed the pieces to him, perhaps in exchange for advertising which was prominent in most editions. Among those was John S. Stark, who allowed one of his ragtime publications or articles to be published in the magazine each month during at least the first year, and sporadically from 1915 on. The bulk of pieces that appeared subsequently were by Christensen or others who taught at his various branches in the Midwest.

The Ragtime Review magazine's subscriber base was eventually bought by publisher Walter Jacobs around 1918, and he incorporated it into his own Melody Magazine, which was largely managed by composer George L. Cobb. The circumstances of this buyout are unclear, but it likely removed some competition for Jacobs as well as giving him a greatly increased circulation. It should also be noted that many others tried to emulate Christensen's publishing and teaching success, and some of the literature for smaller ragtime or piano schools are obviously directly derived, and in some cases plagiarized from the Czar's own work. However, his name dominated the field, particularly in cities where his schools continued to do good business. His Los Angeles branch even claimed a few movie stars in the late 1910s among their clientele.

As ragtime languished and jazz thrived with the approaching 1920s, Christensen quickly adapted, and soon his ragtime instruction books and schools became jazz-oriented. As novelty piano became popular in the early 1920s he added novelty riffs and licks to the course, as well as some novelty compositions of his own. There were even books on how to execute piano breaks in a variety of ways, an indispensable aid to the amateur jazz band pianist. On a few occasions in the 1920s Axel recorded some sides for the Okeh and Paramount record labels. In 1923 he signed a contract with the United States Music Company to record piano rolls of his own works, as well as instruction rolls of the Christensen system. That same year he opened a music store at 526 South Western Avenue in Chicago, featuring musical merchandise, Okeh records, music rolls and radio amplifiers.

Axel

himself ventured out more in the mid-1920s as well, having long progressed beyond being an average pianist, and now even billing himself as a "Pianologist." As reported in the Music Trade Review of January 5, 1924, he announced a tour "featuring recorded numbers on piano." It goes on to say that the "popular and entertaining pianist syncopator, who records exclusively for the U.S. Music Company of Chicago, will being the first of a series of acts in a theatrical tour which calls for appearances at many of the best-known motion picture theatres. He will favor his audience with well-known and snappy piano skits, which are responsible for his popularity throughout the country." One of those was a by then famous parody of the poem "The Face on the Bar-room Floor." He had also worked up a set of "synco-symphonies" for performance.

|

The tour opened at the Circle Theatre in Indianapolis, Indiana, for a two week stay in January 1924. It was presented with the cooperation of and promotion by the U.S. Music Company. As might be expected, many of the pieces he played just happened to be available on rolls in the lobby. He gave his own shows around the country in both private and public venues, and occasionally with vaudeville troupes. Axel's shows were sort of a one-man vaudeville evening with music, singing and stories (no dancing was reported). Among the advertised treats were syncopated versions of classics like the ubiquitous Poet and Peasant Overture. This is in line with his comment that "classical music is one of the finest of arts and dwells briefly upon the original narratives of some of the best-known classics." In the act he also demonstrated how some of these classics were often used as the basis for a popular tune, including his own syncopated versions of such works. Overall, the tour was a success for both the artist and the sponsor, who reported an increase in roll sales in each city Christensen appeared in.

The entertaining Mr. Christensen continued to tour for much of the rest of the decade. In 1925 and 1926 he was put on the popular Orpheum and Keith circuit of vaudeville theaters earning at least $1,000 per week. At that same time, he appeared on many of the earliest radio stations in the country, including KYW (Philadelphia), WEBH, WGN, WMAQ, WQJ and WLS (all Chicago stations). He also recorded some of his ethnic comic monologues used on stage on the Broadway label, a subsidiary of Paramount. Axel attended or hosted many events in Chicago when he was in town. On December 7, 1926, a "stag dinner" was given in honor of the maestro by the Chicago Piano Club which he had joined several years prior. The affair was reportedly a great success, and Piano Club members awarded him with a solid gold pocket watch. In early 1927 Christensen started a series of programs on Chicago station WHT owned by the Wrigley corporation. One of the highlights of the first show was an imitation of the late Bert Williams singing Somebody Else, in addition to his usual comedy.

Axel's regular haunt in Chicago in 1926 and 1927 was the Palace Theater, a movie house which no longer required his services after their conversion to sound in 1928. Over the next three years he continued to regale audiences everywhere on radio and in person with his humorous anecdotes, which more and more took the balance of an evening with less piano playing. A book of many of these stories, Axel Grease for Your Funny Bone, was published in 1930. Also, by 1930, his son Carle had joined the act, performing at the piano more frequently on stage with his famous father.

By the time the Great Depression set in around 1930, Axel's schools and even his publications were likely considered a frivolous expense by most consumers in light of the economic downturn, and he had to scale back the operation. It had clearly become a family business, as in 1930 Mr. Christensen, now living in the exclusive River Forest suburb of Chicago, listed himself as the proprietor of his small empire, with Reine as a manager and Carle, now 20, as an assistant manager. Many of the schools closed, although he still published courses in learning jazz, and later swing music, throughout the decade. Axel still managed to find performance work in the final days of Vaudeville and for many private functions and conventions. By this time, he was promoting comedy, a much needed commodity, as a major part of his entertainments. This included promotional material with examples of his jokes and humorous stories.

Carle Christensen married Alyce Oglozinski in Chicago on April 20, 1931. The couple subsequently moved to California soon after, perhaps to manage a Christensen school there or even pursue an additional degree (the circumstances are still under investigation). Alyce gave birth to Carlos Christensen on March 15, 1933, with David G. Christensen following within a couple of years. However, the couple was back in Chicago at some point later in the decade with Axel and Reine, as Carlos was schooled in Illinois. In the meantime, the elder Christensen switched radio stations in 1934, now performing regularly in WJJD in Chicago. The schools there remained in business throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s. Indeed, an advertisement run in Chicago papers from the summer of 1945 through the following spring promoted the Christensen School of Popular Music, urging the reader to "Learn Swing Piano the Axel Christensen Way." The ads appear to cease around June 1946.

At some after World War Two, the extended family relocated to Southern California. Carle and his brood returned there permanently around 1946 and Axel and Reine followed in late 1947 or early 1948. As related by Chris Christensen, Axel was a strong believer in the Baha'i faith, and there was a particularly notable temple and school in Ojai, just east of Santa Barbara. It does help to clarify why Carle had an Ojai address for many years, and indeed retired there. It also speaks clearly on the strong faith base for the Christensen family that kept them together. The 1950 census showed Axel and Reine residing not in Ojai, but in Los Angeles, his occupation reading as proprietor of entertainment.

According to his grandson David, Axel not only kept on performing in Los Angeles after his move, but made a rare television appearance. He was listed as appearing on KLAC 13, October 4, 1951, on the show You're Never Too Old. Christensen performed all over the Los Angeles area for a variety of functions nearly up to his death. Many were private functions for small civic organizations, and there is at least one notice published as late as April 3, 1955, in a Long Beach, California newspaper. The music school entrepreneur died months later in Los Angeles at age 74 leaving behind a wake of happy people who somehow had managed to learn the joy of ragtime through his methodologies. His wife survived him through 1962.

Carle continued to issue Christensen publications through the mid-1960s. He retired to Ojai and lived there until his death in 1996. Carlos, a music enthusiast by birthright who became a computer scientist in the 1960s, died in the spring of 2007 in Concord, Massachusetts, where he had been collecting memories of his youth with grandfather Axel. David G. Christensen is the sole remaining member of the family who knew Axel, and has followed the Christensen creative bent as producer of video and music projects, residing in Port Townsend, Washington.

[1] Some Ancestry Family Trees have the name Mary Larsen as opposed to Anderson. Demographics are similar, but no marriage record or matching death record could be found for Mary Larsen associated with Charles Christensen. Mary’s death record in Chicago on December 14, 1927, shows her parents to be Lars Anderson and Marie Hansen, and that she was married to Charles C. Christensen, informed by Charles W. Christensen, making Anderson the more logical match.]

Many thanks to Canadian Ragtime historian Ted Tjaden who provided some of the information here to supplement my research, as well as posting many Christensen items on his site, including the entire run of the Ragtime Review. Please visit his site at www.ragtimepiano.ca. Also, Robert Perry for providing the QRS piano roll information and Andrew Barrett on a couple of the recordings. Thanks also to Chris Christensen, the family of Carlos Christensen, and David G. Christensen for some additional clarifications.

Of particular help has been research done on the Saint Louis branches of the Christensen schools by Bryan Cather of the Scott Joplin House in Saint Louis, including Axel's link with publisher John Stark.

Some additional information is provided in the book That American Rag by Dave Jasen and Gene Jones, which should be in every ragtime enthusiasts' library. The rest was uncovered by the author in public records, periodicals, and other varying sources.

Compositions

Compositions