Leland Stanford Morgan June 9, 1886 to August 12, 1981) | |

Selected Covers (Hover to View) Selected Covers (Hover to View) | |

Named after the famous business tycoon, railroad investor and California Senator [leaving behind a nefarious reputation], Leland Stanford Morgan would eventually become known for his artworks and teaching in the field, but his initial story did not point in that direction. He was born in 1886 California to lumber yard clerk Alvin Nelson Morgan and his wife Margaret Ann Carberry (some sources show Donnion as her last name). Although four other siblings were born during the 1880s, only one other survived, his brother George Nelson (1/22/1885). It is not clear why Alvin left Illinois for the west in the early 1880s, but even thirty years after the famed California Gold Rush had subsided, there was still plenty of opportunity for enterprising individuals. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, San Francisco directories showed Alvin working as a clerk, yardman, and even foreman of a lumber yard, as did the 1900 census taken in the city.

Eventually becoming a lumber surveyor, Alvin was able for afford a moderately good education for his sons. After secondary school, Leland attended the California Business College in San Francisco, graudating in December 1903. He had also developed some skill in art, painting and sketching during those years, which helped to lead him into a career in - insurance. However, a later article from 1938 indicates the possibility that he had gone to Chicago, Illinois, for a while, looking for work that would allow him a couple of nights of training at the Art Institute there. The timeline on this is uncertain, but the 1903-1905 time frame is the best fit.

Eventually becoming a lumber surveyor, Alvin was able for afford a moderately good education for his sons. After secondary school, Leland attended the California Business College in San Francisco, graudating in December 1903. He had also developed some skill in art, painting and sketching during those years, which helped to lead him into a career in - insurance. However, a later article from 1938 indicates the possibility that he had gone to Chicago, Illinois, for a while, looking for work that would allow him a couple of nights of training at the Art Institute there. The timeline on this is uncertain, but the 1903-1905 time frame is the best fit.

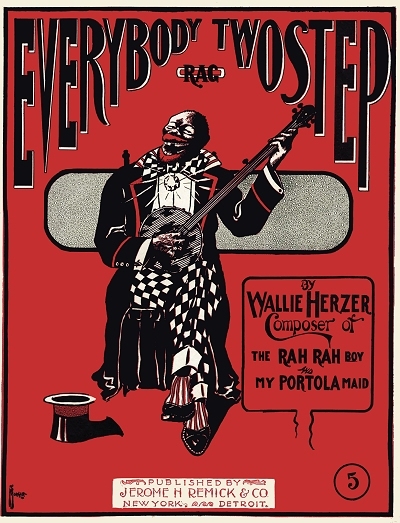

San Francisco directories from 1905 to 1909, and the 1910 Federal enumeration, all indicated that Leland was working as a bookkeeper or clerk at the insurance firm of Christensen and Goodwin. Still living with his parents and brother, it appears he soon had a change of heart in terms of pursuing his skill set, and in the 1910 San Francisco directory published mid-year, Morgan was listed as a cartoonist. The following year's directory elevated him to the status of artist. It is unclear what publications he may have been contributing to at the time, but there were plenty of newspapers and even a few magazines based in the Bay Area with which he may have done business. Around 1912 Leland migrated across the Bay, settling in Oakland, California, now working as an illustrator. In addition to the occasional book, he started providing sheet music covers in the early 1910s, largely to local publishers, although a couple of them managed to make it to New York via acquisition. The most widely-circulated of those graced the covers of two compositions by Wallie Herzer, a sometimes-composer who was also working in insurance and, in fact, at the same firm as Morgan. When the self-published The Rah-Rah Boy and Everybody Two-Step gained some circulation and the latter piece was released on records, they were both purchased by New York publisher Jerome H. Remick in 1911, including the plates and original cover. This may have encouraged Leland to continue in this field, in addition to his other illustrative pursuits.

During the 1910s Morgan contributed covers to many Bay Area publishers, the most frequent client being Buell Music, a vanity firm run by composer Joseph Buell Carey. However, he also managed some fine work for piano manufacturer and music store Sherman, Clay & Company, Daniels and Wilson run by veteran composer Charles Neil Daniels, and Nat Goldstein Music. While he did not profess to a particular speciality, a number of the pieces with Leland's covers were exotically-themed, showing partially sillhoueted scenes from Hawaii and the Orient. In spite of his other work in California newspapers and magazines, these remaing the most widely circulated and enduring images from Morgan's hand. In early December, 1915, Leland was married to Ruth Vivian Holloway in Oakland in a secret ceremony. Family plans for a large Christmas holiday wedding were shattered and abandoned by their families after this event. Leland's June, 1917, draft record taken in Oakland showed him working as an illustrator on his own account. A notice in the Oakland Tribune of October 6, 1917, indicated that he was deployed to the army camp at American Lake, but little else was found on his service during World War I. There is a possibility he remained stateside, since some illustrations show up on 1918 publications.

Once Leland was out of the service, he decided to pursue a more stable career, possibly because most of the country's working artists were currently in the East rather than California. In 1918, he and Ruth moved southwest to Fresno, California, where he worked as an insurance adjuster. However, by 1920, he was employed as a salesman for a wholesale tire company, as indicated in some directories and the 1920 Federal census. It was in Fresno that their daughter Merle Marcella was born on November 7, 1919. Son Alan Edgar would come on April 1, 1922. While the Morgans moved back to Oakland in 1921, Leland remained in the tire and rubber business as a salesman over the next decade, while keeping his art activities to the side. The 1930 enumeration, taking at the leading edge of the Great Depression, had him in the same role. It is possible that either the tire business was less lucrative or profitable during the Depression, or that he simply wanted to go back to his first love. So that same year, Leland jumped back into a career art in a big way, as noted in this announcement from the Oakland Tribune of August 30, 1937:

Art Institute of Oakland, which is now in its 16th year, was established by Elton Fox in 1921 and operated uner the name of "Fox Art Institute and School of Commercial Art." Leland S. Morgan became associated with Mr. Fox in 1930 and reorganized the Fashion Art Course. The school was then called "Fox-Morgan Art Institute and Commerical Art School." In 1935 Mr. Fox went to Australia and Mr. R.C. Dean became associated with school for two years. Mr. Morgan, who has been teaching Fashion Art and Commercial Art continually for the past seven years, is in complete charge of the Art Institute. Visitors Are Always Welcome. 339 15th Street.

Voter registries from 1932 forward to at least 1944 also indicate Leland as a commercial artist, and the 1940 census listed him as the owner and teacher of a commercial art school. One incident from December 1938, reported in a syndicated article in national newspapers, showed his sympathy for youth who were in his position when he was young. A Jewish youth named Leopold, who had been exilied by the NAZI party in Germany, came to the United States with only his talent and a desire to draw. Morgan was exposed to his talent as an artist, and offered to give him 12 months of training for free, focusing largely on advertising art. He stated his theory that a good position was difficult to obtain without the proper training. This story obviously generated good will for Leland and his school, but only touched on the issue of Jews in NAZI Germany, most of which would come to light within seven years.

Ruth passed on in 1939, leaving Leland a widower. The 1940 enumeration was ambiguous as to his status (M for married is crossed out with a 7 next to it), but their chldren, both now students at the University of California Berkeley, were still residing with Leland. Around this same time he had been introduced to an Ann Arbor, Michigan, artist of some note in oils and watercolors, Alice E. Smiley, a recent divorcée. She had been caring for her ailing mother in Oakland when they met. They were married in Reno, Nevada, and moved into a new residence in Oakland after a honeymoon in Yosemite National Park. It is not certain if the union lasted, as Morgan's 1942 draft record, on which he had curiously altered his birth year to 1891, made no reference to Alice, but rather to his daughter, now Mrs. J.B. Saunders, in Berkeley. The only employment listed was Art Institute. The 1950 enumeration, taken in Oakland, showed Margon to be the proprietor of his own art school, and yet another wife, a Minnesota native named Mary E., working as a saleslady in a department store.

Leland ran the Art Institute and his Morgan School of Fashion Art for several more years, then all but disappeared from view by the late 1950s. He died in Oakland in 1981 just short of age 95. Today, although his covers are less known than those from New York or Chicago publishers, they still see circulation among those in the ragtime and early popular song communities. Signing most of his covers as LE MORGAN, his work was often simple in structure, focusing more on the subject than the background, and using basic color palettes. Many of them might be considered as sillhouettes with details filled in, while others were actually relatively well-rendered landscapes. In some ways, it set apart West Coast publications from their eastern counterparts, and his work still grabs attention a century later.